A History of Alcatraz

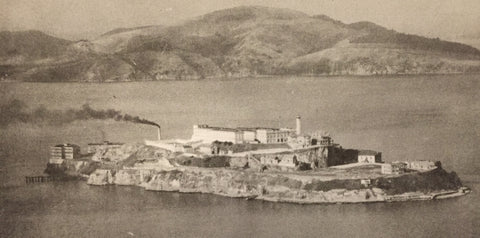

The 12-acre rock-island lies in the middle of the world's largest natural harbor. When one walks the hollow corridors today, especially on those fog shrouded days the island knows so well, the echo of desperate footsteps resonates from the past. A penetrating chill seeps through the old brick walls, a souvenir of more solemn days.

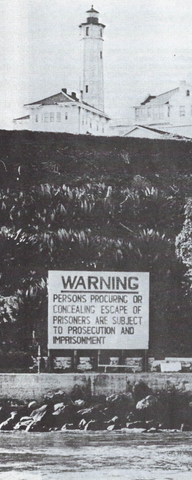

It is an island of curious and protective "firsts." The first lighthouse on the west coast was located on this island, a marker to guide the tall ships to safety. The U.S. Army established the first west coast garrison on this misbegotten island. They built heavy fortifications and constructed tactical batteries to strategically form a "cork" of cross-fire in the narrow Golden Gate. Notoriety for Alcatraz came with the Federal Penitentiary, different from other penal institutions in that its chief design was to hold the incorrigibles, the bad and the bold; a basket for the most rotten of apples.

The history of the little island in San Francisco Bay is very well chronicled. Discovered by the Spanish land expedition of Portola in 1769, it took six years until a Spanish ship managed to find its way through the Golden Gate to chart the bay. (Despite intense exploration at sea, the Spanish and English explorers had missed San Francisco Bay!) It is thought that the location of Alcatraz in the middle of the bay when seen from the sea, forms an illusion of landfilling in the Golden Gate. Charts and records of the period show the Golden Gate as a small cove. At the time of the charting, the barren island was white with pelicans and their guano; thus it was named Isla de Alea traces or the island of the pelicans. The 1846 transfer of the title by the governor of California to Julian Workman reads: ". . . a small island called Alcatraces ... which has never been inhabited by any person or used for any purpose ... " Workman won the scramble for the island because he proposed the construction of a lighthouse to aid the navigation through the Golden Gate; a feat that was finally accomplished by the U.S. Army Engineers in 1854, while building their fortress.

This fortress boasted three batteries of long-range cannon, bomb-proof magazines, and a 35-foot-high brick citadel. The high citadel allowed observers a clear view of every point-of-fire around the island. The current prison building was built on what had been the underground quarters in the citadel.

Fine-grained sandstone rock makes up the island and is not hospitable for much vegetation. In fact, the island was barren except for some hardy grass, moss, and kelp. The army brought soil and plants after the construction of the citadel. Having no source of water or any springs, the military built large stone cisterns throughout the citadel. These were also incorporated in the foundation of the cell house. They led to the rumors of the damp dungeons below the prison.

As the fortress outlived its usefulness in defense of the bay, the walls were employed as the military stockade. Finally, the main body of the main garrison was deployed to the Presidio, Fort Baker, and Angel Island. Alcatraz was designated as the Pacific Branch U.S. Disciplinary Barracks. Some modification of the citadel was done at this time. In fact, the original building had been changed throughout its existence during the end of the nineteenth century. The island survived the great 1906 earthquake with little damage. It was used to house the city's prison occupants until stability returned to San Francisco.

The Depression brought hard times to many, including the War Department. Money was tight, and costly operations were being scrutinized. Alcatraz was costing the military too much. The late '20s and early '30s brought a wave of crime throughout the entire nation. Nurtured on the lucrative bootlegging and speakeasies of the Prohibition Era, gangs and mobsters turned to more violent crimes: robbery, kidnapping, murder, and extortion. Amateurs driven by desperate need found easy money worth the risk of being caught. Prisons were crowded. Daring escapes, gang murders, and mass rioting were a menace to an orderly prison.

Attorney General Homer Cummings supported J. Edgar Hoover and the F.B.l.'s determined pursuit of criminals, but he realized there had to be a facility to safely control and incarcerate. It seemed that the more notorious the criminal, the greater the likelihood that the mobster would be "sprung" by supporting gang members. John Dillinger was a prime example. While on parole in 1933, Dillinger master minded the escape of ten inmates of the Indiana State Prison. All were former members of the Dillinger gang. Several months later, three of the escapees returned the favor shooting a sheriff in Lima, Ohio and releasing Dillinger. In June 1933, the country was stunned by the bold shoot-out, with F.B.I. agents, in an attempt to release Frank Nash, an escaped convict. Five officers died and two were injured seriously. Murderers, thieves, kidnappers, and hijackers became organized.

The head of the federal prisons, Sanford Bates. worked closely with the attorney general in a bold concept. Isolate the agitators and influential criminals in one institution. To find that the nexus of a maximum-security prison stood ready to be abandoned by the federal government must have seemed incredible.

What was to become the main prison building, was built from the foundations of the citadel. The citadel had been torn down. The last major changes were when the army transformed the building into a disciplinary barracks. Still, extensive work had to be done to upgrade and secure the facility.

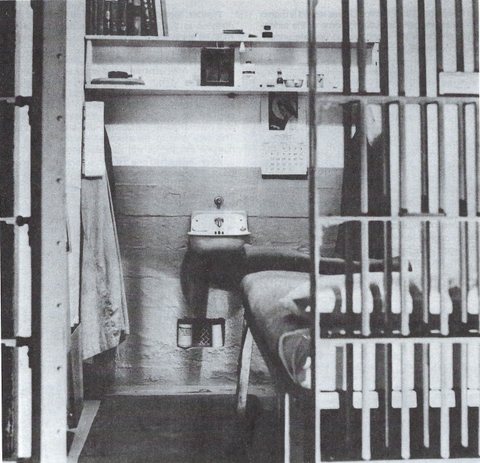

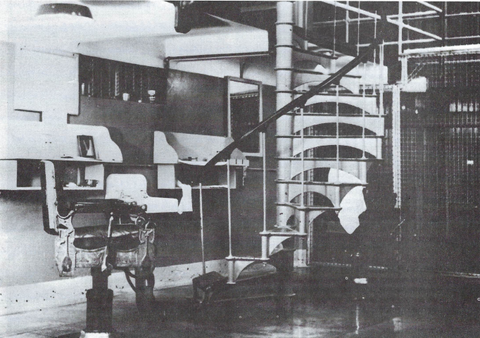

The soft steel bars, which had been used in the front of the cells, were replaced with tool-proof bars; but only on half the cells, predominantly on Band C blocks. The budget was very tight, though in ironwork alone the bill was $216,927 (exceeding the original cost of the prison). Electric doors were installed on several cells for maximum security. Prisoners would be restricted to specific areas within the compound. They weren't given the run of the island, as had the military prisoners. Traverse tunnels were sealed. Windows were covered with tool-proof steel. Gun galleries, running the height of the prison complex, and located at either end of the blocks, were built and enclosed by steel bars. It had been decided to use just the two main cell-blocks (B and C). Each cell-block had three tiers, 58 cells per tier, yielding 174 cells per block, and 348 total. (D block was later incorporated for isolation.)

The original transfer from the War Department to the Justice Department called for the maintaining of the laundry facilities on the island to care for the area's army laundry needs. Freshwater would be provided by the army's boats, though the Justice Department had to pay its share of the expense.

Security was extremely important. Bates wanted the inclusion of a tear-gas system, built into the ceilings of the cell-blocks and the dining area. The concept was to have only the perimeter guards armed with guns, leaving the floor with gas-billies. Metal detection devices were installed at the entrance to the administration building by the door to the dining hall and between the work areas and the stairs used by the workers to and from the cell blocks. Their accuracy was forever in doubt. Wire mesh fencing was placed around the work areas. Barbed wire was strung around the perimeter fences. Towers were constructed and equipped with high-intensity lights overlooking the dock, the gate entrance to the work areas, the top of the administration building, behind the power plant, and over the yard. Another tower was requested, on the outer portion of the shop area, as there was no observation point for this "blind" area. The budget could only provide that steel mesh be placed over the windows on that side instead. (This proved to be a favored escape point and was later remedied.)

The physical facility was renovated, the natural barriers were excellent; chilling bay waters and prohibitive currents. The only thing missing was the human "walls" of the prison. James Johnston was asked to fill the role of warden in October of 1933. He had been warden of San Quentin and Folsom prisons and maintained a high reputation for rehabilitation and integrity. Warden Johnston served from 1934 to 1948, followed by Edwin Swope (1948-1955), Paul Madigan (1955-1961) and the last, Olin Blackwell (1961-1963). Johnston set the tenor of mystique in his application of the rules and format for the operation of the prison. He selected the best guards and officers from the federal penal system. They were all given special training at McNeil Island in Washington.

In December 1933, Sanford Bates issued a memo to the attorney general outlining some of the fundamental principles the island was to operate under:

- All privileges to inmates would be limited.

- Visitors are to be earned, with no visitation allowed in the first three months of a convict's residence, and when earned limited to one visit per month.

- No parole officer would be appointed and no regularly scheduled parole board meetings were to be held.

- Inmates can obtain attorneys only through application to the attorney general.

- Prisoners were to come to Alcatraz through other penal institutions. There would be no direct commitments from the courts.

- While a usual library would be provided, there would be no newspapers, magazines, radios or other forms of entertainment allowed.

- No original letters were to be delivered to inmates; only typewritten copies of letters after they had been screened.

Warden Johnston added a few ramifications and nuances to the basic design sent to him. Visitors must be family and limited to two people per monthly visit. One prisoner per cell was the original design. The 5 x 9 x 7 cells were equipped with a steel bed with a mattress, a foldout table and chair, two shelves, a toilet, and a sink. This was to prove to be a luxury to many, as most inmates were used to four or even six per cell. From 1934 to 1940 Johnston established and maintained a "no talking" rule in the cell house. This was later to be assessed as one of the in humane treatments and was suspended. All privileges had one thing in common, they could be taken away. At first, the only work done on Alcatraz was the operation of the laundry for the military and the basic maintenance of the island. Warden Johnston noticed, very early on, that the inmates who were allowed to work, took great pride in what they did. It became apparent that the tedium of incarceration was the hardest row to hoe for the prisoners. Eventually, several additional operations were put into effect.

There was corporal punishment on Alcatraz - at least as much as in the other federal penitentiaries. Despite rumors of deadly dungeons, Johnston used subterranean rooms (the old storage areas in the citadel) as isolation cells, but the walls were so loose that prisoners had to be shackled to the ceiling. Eventually, D block was used for isolation, though prior to its renovation one escape attempt from this unit occurred.

It had been decided that the wardens of all the federal prisons would select inmates from their populations for transfer to Alcatraz. The guidelines were simple: send the most troublesome prisoners, gang leaders, escape artists and prisoners with long and / or violent prison records. They were transported by train, at first in large groups, and later one at a time. It was 5:00 a.m. Sunday morning, August 18, 1934, when the final passenger boarded the specially modified train in Atlanta. Fifty-three of the most dangerous and influential prisoners at Atlanta, including Al Capone, were on their way to San Francisco. They had boarded the train just outside the prison walls. They would follow a special route stopping only for maintenance and crew changes, under strict security and with no publicity. The train was switched to approach the bay from Marin County, bringing it to the quiet community of Tiburon. From there the cars were loaded onto a barge and brought to the Alcatraz docks. It had been virtually a door-to-door trip.

These were not the first prisoners to enter the penitentiary. The army had left 32 prisoners in federal custody as of July 1, 1934. Fourteen inmates had been transferees from McNeil Island on August 11th. That allowed Warden Johnston and his men a "rehearsal" of handling the prisoners. The last mass movement of prisoners brought "Machine Gun" Kelly and 102 others from Leavenworth and Leavenworth Annex.

Prisoners adapted quickly to the new routines. The intense security measures were the first outstanding change. There were 13 official headcounts in each 24-hour period plus six verification counts. Random counts were thrown in. Bathing and clothing changes were scheduled for twice a week and heavily regimented (Prisoners working in the kitchens bathed daily.)

Recreation was extremely limited. The recreation yard was limited in size, allowing baseball, horse shoes, dominos, and various card games. The only other recreation was to be found in the prison library. Here the Justice Department had inherited the army's collection of novels and when supplemented with Warden Johnston's allocations, Alcatraz boasted a most diverse library.

Another outstanding feature of Alcatraz was the food. The nutritional value and quality were highly touted. Even throughout the rationing of foods during World War 11, the prison maintained a very good kitchen. Prisoners were given full freedom to select what they wanted from a posted menu for each meal, but the waste was not allowed. A prisoner who wasted food was quite often denied his next meal. In the first few years, the rule of silence applied to the dining hall, but this proved very hard to enforce. The time allowed for eating, like every other aspect of life on Alcatraz, was regimented: approximately 20 minutes per meal. Eating utensils had to be placed on the trays in a prescribed manner, and each tray was checked prior to the dismissal of the prisoners from the mess hall.

The monotony of the routine served to irritate many of the inmates, despite the simple diversions of the library and their jobs. For these people, the warden would counsel: "Take each day of your sentence, one day at a time. Don't think how far you have to go, but how far you've come." While the attention and advice helped many, it never eased the tedium.

Special thanks to:

- Text By: James Fuller

- Research and Editor: Yumi Gay

- Taylor Flores